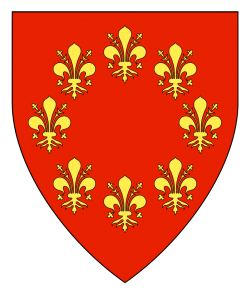

Lady Angelica is an established member of the society, serving as the chatelaine of the Canton of Whyt Whey, but had never registered her name or arms, an oversight I was pleased to help correct.

Gules, eight fleurs de lys in annulo Or.

In our first round of consultation, Angelica identified red and gold as her preferred colors, and the Florentine fleur de lys as her desired primary charge, but pinning down the optimum arrangement required multiple iterations before this design emerged as the favorite.

Angelica di Nova Lipa is the name of a Northern Italian woman during the Renaissance whose family hails from the Slavic village of “New Linden” on the other side of the Adriatic Sea.

Angelica appears as a woman’s name in many parts of Europe during the late medieval period, including in northern Italy and adjacent areas of central Europe.

“Angelica” is a Florentine woman’s name dated to 1427. (In “A Listing of all Women’s Given Names from the Condado Section of the Florence Catasto of 1427” by Juliana de Luna.)

“Angelica” is a Roman woman’s name dated to 1527. (On p. 87 in “Sac de Rome,” by Jacques Bonaparte, 1830. Image)

“Angelica” is a Venetian woman’s name dated to 1615. (In “Names from Sixteenth Century Venice” by Juliana de Luna.)

“Angelica” is a Hungarian woman’s name dated to 1230/1356. (In “Nıi neveink az Árpád-korban” by Edina V. Jurkó, at University of Debrecen’s Department of Hungarian Linguistics.)

di <placename> is a rare but attested form for northern Italian names. (SENA Appendix A states “Locative bynames in the northern and central areas normally take the form da X, but de X and di X are rarely found.”)

Italian and South Slavic name elements may be used together for the period of 1100-1600, according to SENA Appendix C.

Nova Lipa is a village between Vinica and Črnomelj in the White Carniola region, adjacent to the historic Venetian province of Istria, now part of modern Slovenia. In the Slovene language, the name means “new linden” (like the tree) and is distinguished from Stara Lipa (“old linden”), another village centered one mile to the north. (There are also paired adjacent villages named Nova Lipa and Stara Lipa a hundred miles to the east, in modern Croatia.)

While we haven’t been able to find a period source that refers to the village by this exact name prior to 1600, we believe it has been continuously occupied for more than a thousand years, and has been known by this name for more than four hundred years, as shown below.

The area of the village has been inhabited for thousands of years, and was previously the location of a Roman-era settlement. (Archeological site identified in 2006; Image.)

The area of Nova Lipa and Stara Lipa are listed together in fourteenth and fifteenth-century German-language texts as Linten, Linden, Lindenn, Lynden, or Lindenn, with references such as “dacz der Linten”, 1334, and “czu der Lindenn,” 1463, both found under the heading “Nova Lipa, pri Vinici v Beli krajini” (or in English, “Nova Lipa, near Vinica in White Carniola”), in “Historična topografija Kranjske (do 1500)” by Miha Kosi, Matjaž Bizjak, Miha Seručnik, and Jurij Šilc, at the Milka Kosa Historical Institute. (Image)

The linkage of these historical listings to the modern location of Nova Lipa is justified by an accompanying note: “Lokalizacija glede na [Urb. Nemškega viteškega reda, f. 216] iz 1490, kjer gre očitno za Staro in Novo Lipo” (or in English, “located via page 216 of the ‘Estate Records of the Teutonic Knights of 1490,’ where it is clearly for Stara Lipa and Nova Lipa”), citing “Urbar Nemškega viteškega reda za posest v okolici Ljubljane, Metlike, Črnomlja in Velike Nedelje 1490,” Codex 164 at the Central Archive of the Teutonic Knights in Vienna, which provides a listing of properties owned by Teutonic Knights in the vicinity of Črnomelj.

These listings of Linden are recorded in German, the language of the ruling Habsburg family and other elites, but local farmers in the fourteenth century would have spoken a Slavic language, a predecessor of modern Slovene, in which the village name would have been “Lipa.” For example “de Lipa” appears as a locative byname for numerous Czech men in 1310–1404. (Including “Heinrecus de Lipa 1383-1386” p. 43, and “Wenceslaus pernář de Lipa 1404” p.171 in “Registrik jmen osobnich”, a registry of personal names, by Wacslaw Wladiwoj Tomek, 1875; Image, Image.)

Although all of the residences in the area were originally considered to be a single village, some of the homes eventually formed a separate cluster on the southern side of the valley as residents shifted buildings to the hillsides to preserve open land for farming. (A sociological survey of patterns of town organization in the local area states that “Vas Nova Lipa (Bela krajina) je zato, da bi se ohranila rodovitna zemlja v bližnjem podolju, pomaknjena na višji, močno vrtačast svet, kjer hiše stojijo med vrtačami ali tik ob njih.” or in English, “New Lipa village (White Carniola), in order to maintain fertile soil in a nearby valley, moved higher, to an area of karst depressions where houses stand between sinkholes or adjacent to them.” In “Morfologija Vaških Naselij v Sloveniji” by Vladimir Drozg, 1995; Image.)

This southern group of buildings was soon recognized as a distinct place known as “Nova Lipa,” growing large enough by the 1600s to justify construction of its own church, the “Nova Lipa Church of the Holy Spirit.” (“Nova Lipa Cerkev sv. Duha,” dated to the 17th century by the Slovenian Cultural Ministry; Image.)

Although we do not have an exact date for the church’s construction, the village would have existed for a number of years prior to the building of the church, as churches were only erected in established population centers. Dr. Miha Kosi, a Slovenian historian with expertise in medieval geography of the region, believes the village was formed prior to 1600, during the Renaissance period: “When the village was divided, i.e. Nova Lipa was established, I don’t know, but obviously only after the middle ages, but before 17th c. (the building of the church of Holy Spirit).” (Personal communication, June 2017; Image.)