Sara and Giuseppe live in our neighboring barony of Dragonship Haven. Her name and arms had been registered but she wanted to tweak them, while his were being registered for the first time.

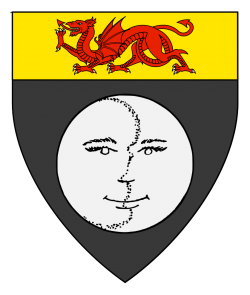

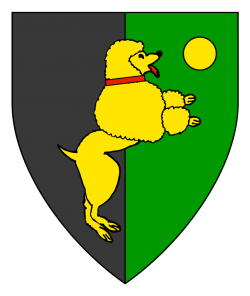

Per pale sable and vert, a poodle salient contourny Or, collared and langued gules, and in sinister canton a bezant.

Sara already had similar arms registered, but with a talbot sejant, which she wanted to swap for a poodle salient.

Poodles are documented as period, being known from at least the fifteenth century. The poodle illustration is adapted from the submissions of Briana Heron of Caid, using the period shearing for water dogs without ornamental pompoms.

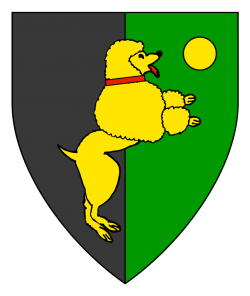

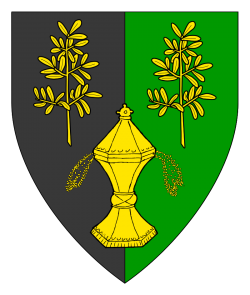

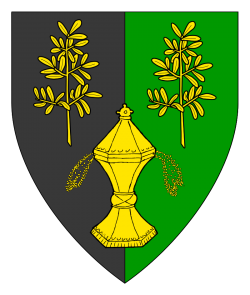

Per pale sable and vert, two sprigs of rue and a covered salt-cellar shedding salt Or.

Giuseppe wanted his arms to share a common field with his wife’s, but wasn’t sure what charges it should bear.

After a bit of brainstorming, I came up with a cant on the household name “Salaparuta” or “Sala di Paruta” using the medieval name for a covered salt shaker, and the Italian/Latin word for common rue: “above a salte, a pair of rutas.”

Canting arms, using rebuses, puns, and alliteration, were very common in medieval heraldry, being well adapted to a society with low literacy but a taste for symbolism and wordplay.

Sara Sala di Paruta

Sara is an Italian form of the common female name Sarah, attested in Sicily in the 15th C.

S.n. Sara, “… Ma può risalire direttamente alla forma ebraica Sārāh; cfr. Sara mulier iudea uxor quondam Buxacce, a.1400.” Found in “Dizionario Onomastico della Sicilia”, Caracausi, G., 1994, Palermo. Translation by Maridonna Benvenuti: “But it can be directly traced to the Jewish Sārāh form; cfr. Sara mulier iudea uxor quondam Buxacce, year 1400.”

SENA Appendix A states that Italian names may take an unmarked locative byname. Sala di Paruta was the medieval name of a village and associated castle in Sicily that is currently known as Salaparuta.

Giuseppe Sala di Paruta

Giuseppe is an Italian form of the common male name Joseph, attested as the name of a Sicilian living in Rome during the 16th C.

“Giuseppe Sicilano” is one of many men named Giuseppe listed in “Names of Jews in Rome In the 1550’s” by Yehoshua ben Haim haYerushalmi, drawn from Nota Ebrei, a 16th C. rabbinical archive.

SENA Appendix A states that Italian names may take an unmarked locative byname. Sala di Paruta was the medieval name of a village and associated castle in Sicily that is currently known as Salaparuta.

Sala di Paruta

Sala di Paruta was the name of a village and an associated castle in medieval Sicily.

When the first tower of the castle was built in 1296, it and the village were known as “Sala Della Donna” (“Hall of the Lady”). The castle became the seat of a barony known as Baronia Sala Della Donna (“Barony of the Hall of the Lady”).

In 1462 it became the feudal lands of the Paruta family, and shortly after 1500 they renamed the castle and the associated barony “Sala di Paruta” (“Hall of the Parutas”).

In 1561, following the death of Giovanni Matteo Paruta, who had been Baron of Sala di Paruta, his daughter and only heir, Fiammetta Paruta, wed Giuseppe Alliata, who became Baron Sala di Paruta. (Their son was later named Duke Sala di Paruta.)

Throughout this period, the village that surrounded the castle was known by the same name, Sala di Paruta, but during the eighteenth century, the name was combined into a single word, “Salaparuta”, which is its modern name.

Below are three references in history books attesting to the existence of the territory, castle, and/or barony named Sala di Paruta.

Pervenuta veidesi finalmente questa gran Baronia in potere di Giolamo Paruta, il quale nel 1503, accrebbe di novelle fabbriche l’Abitato della vassalla Popolazione esistente in quella, che oltre più d’ un secolo traeva la fua forma (a: Amico Lexic. Topograph., Sic. Vol Mazar. V. Sala Paruta), e però ove fi disse nella mia Sicilia Nobile, essere stata ella edificata da Antonio Paruta nel 1507, fu uno de i sbagli, che mi fece prendere l’ autore genealogico, da cui ne fu cavata la notizia (b: Mugnos Fam. Paruta t. 3. f. 15. ma il millesimo citato del 1507, che volea dire 1503, fu error di stampa, poiché nel mio manuseritto originale 1503. cosi segnato leggesi.) Dalla Famiglia di Paruta cominició ad appellarsi la detta Terra col novello nome di Sala di Paruta, suppressovi l’antico di Sala di Madonna Alvira, e dalli Signori di Paruta fece passaggio ne i Signori Agliati.

— From “Della Sicilia Nobile“, by Francesco Maria Emanuele e Gaetani, 1775, p 263, citing “Lexicon Topographicum Siculum”, by Vito Amico, 1759.

English translation of key passage: “From [1503] the Paruta family began to call this land by the new name Paruta Hall, dropping the old name Hall of Lady Alvira…”

Alvira Giano Andrea suo primogenito, che a’investi Onofrio ed avo dell’ultima dei Paruta, la Fiammetta, con la quale passava di direitto nel 1561 nella casa Alliata la baronia sposando essa Fiammetta un Giuseppe Alliata: la quale baronia già sotto di Girolamo dopo il 1507 aveva preso nome di Sala di Paruta, o Salae Parutarum, sostituito al primo di Sala donne o Sala di Madona Alvira.

— From “Archivio Storico Siciliano“, published by “Scoieta Siciliana Per La Storia Patria” with “Scuola di paleografia di Palermo”, 1889, p 272.

English translation of key passage: “The barony had already under Girolomo from 1507 taken the name of Paruta Hall, or Salae Parutarum, replacing the earlier Hall of the Lady or Hall of Lady Alvira.”

Giuseppe Alliata… Sposó Donna Fiammetta Paruta, figlia di Giovanni Matteo, Barone della Sala di Paruta. Dotali in Notar Giacomo Scavuzzo di Palermo, li 6 maggio 1561; il matrimoni fu celebrato nela Parrocchia di San Giacomo la Marina di Palermo, li 8 successivo.

— From “The History of Feuds and Noble Titles of Sicily From Their Origins To Our Days, Volume Nine”, by Francesco San Martino De Spucches and Mario Gregorio, 1940, p. 292.

English translation: “Giuseppe Alliata… Wed Lady Fiammetta Paruta, daughter of Giovanni Matteo, Baron of Paruta Hall. Dowry recorded by Giacomo Scavuzzo of Palermo, May 6, 1561; the wedding was celebrated in the Parish of St. James the Mariner of Palermo on the 8th.”